How Different is the Opioid Crisis from the Crack Epidemic?

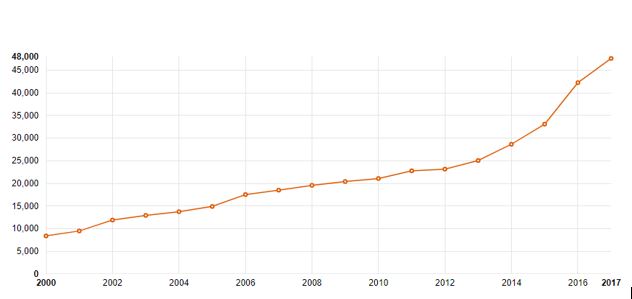

Several years ago, Prince was found dead in an elevator in his Paisley Park home/studio. The cause of death was found to be opioid overdose-specifically fentanyl. As fans debated how true this was or floated various conspiracy theories behind the death of this prolific genius, one thing was clear: his death was among thousands of deaths by the same substance that year. In 2016, the number of deaths caused by opioid overdose was a staggering 42,249 people. By 2017 that number would rise almost 13% to 47,600 deaths. Between 2000 and 2017, 391,152 people died from opioid overdose in the U.S., or more than the population of Cleveland, Ohio.

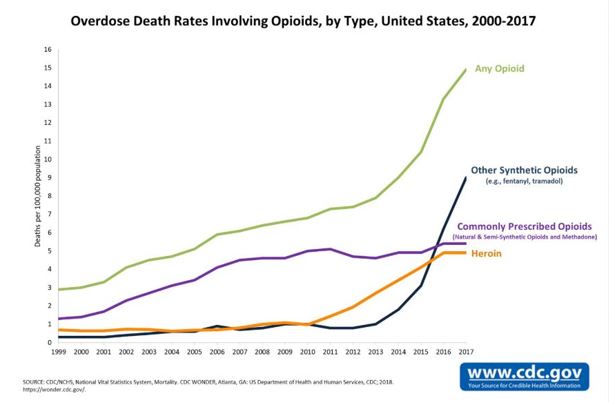

United States Opioid Death Rates, by Type, 2000-2017

Data Source CDC

The Number of United States Opioid Deaths, 2000-2017

Data Source Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

How Bad is the Opioid Crisis?

Public health officials from the local to the national level of government can’t seem to get a handle on this crisis as the number of deaths keeps rising. This is a part of the larger drug/suicide crisis that has sparked a decline in U.S. life expectancy for three years in a row-the longest sustained decline in life expectancy since the period 1915-1918-marked by the flu epidemic and World War I.

How Different was the Crack Epidemic?

There are many crying foul with how the media and some policymakers have responded to the opioid crisis compared to another devastating drug crisis not too long ago: the crack cocaine epidemic. Crack cocaine first hit the big cities in the early eighties and over the next decade in a half spread to much of the U.S. Hundreds of thousands of people became addicted and overdosed on this highly potent form of cocaine. Then-President George H.W. Bush in his first address from the Oval Office, holding a clear plastic baggie of crack cocaine, said “This is crack cocaine, seized a few days ago by drug enforcement agents in a park just across the street from the White House,” he said. “It’s as innocent-looking like candy, but it’s turning our cities into battle zones.”

He would go on to spend $45 billion in a war on drugs. During the ’80s and ’90s when mostly black and Hispanic families were struggling with a family member or members with a crack addiction, the national media narrative was mostly anti-sympathetic towards the users/addicts and even more negative towards the crack dealers. With this epidemic, violence increased in black and brown communities across the U.S. A whole narrative developed around ‘crack babies’ and what the nation could expect as these babies grew up. The governmental response mostly saw the epidemic with a criminality lens, employing harsh sentencing and a call for more prisons.

Federal Response to the Crack Epidemic

In 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which established mandatory minimum sentences triggered by specific quantities of cocaine. It also established harsher penalties for crack cocaine offenses compared to powdered cocaine offenses. If a person was found distributing five grams of crack cocaine, they would get a mandatory five years of prison time, the same amount of time a person would get if they were found distributing 500 grams of powdered cocaine. Before this law was enacted, the average federal drug sentence for blacks was 11% higher than federal drug sentencing for whites. Four years after the enactment of the law, the average federal drug sentencing for blacks increased to 49% higher than that of whites.

Many say the sentencing disparities reflected how race was a factor; from the media/public response to the users/addicts/dealers to how the crisis should be dealt with. In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the sentencing disparity from 100:1 weight ratio to 18:1 and eliminated the mandatory minimum five-year sentence for possession of crack cocaine.

Opioid Crisis is the Worst Drug Epidemic to Hit the U.S.

While many in the media and the American public are more sympathetic to opioid addicts, people are still dying. Public health officials agree that the opioid epidemic is by far the worst drug epidemic the U.S. has experienced. Why are the number of deaths increasing and are projected to see even more increases? It’s simply a matter that the U.S. is NOT prepared for this drug epidemic. The U.S. had an opportunity to get behind drug epidemics first with the crack epidemic in the 80s and 90s and again with the meth crisis that came a little later. Many say the race and class of the addicts informed the response to the past major drug epidemics: one having 84% black users/addicts and the other having a large percentage of lower-income users.

If the U.S. had responded to the crack epidemic in the 80s by investing in drug addiction treatment, there would be a foundation today and this could have slowed down the spread of addiction and thousands more murders that were associated with the sale and distribution of the drug. Maybe we might not have seen so many deaths from opioids.

Is There a Federal, State or Local Response to the Opioid Crisis?

Unfortunately, because there is no major planning for how to effectively deal with this crisis, states may still use their criminal justice systems to deal with the problem. While police and prosecutors have been encouraged to get tougher on drug addiction, at this time we are not seeing the same rhetoric seen during the crack epidemic period.

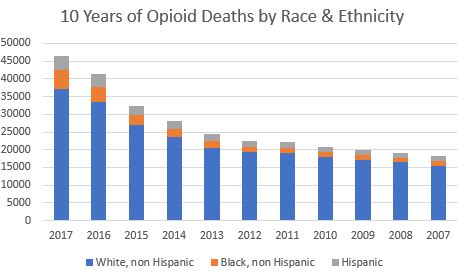

Opioid Deaths by Race and Ethnicity Going Back Ten Years From 2017

There is not much breakout crack cocaine epidemic-related data. This may be a result of crack being a derivative of powder cocaine and any data sources would combine with cocaine datasets.

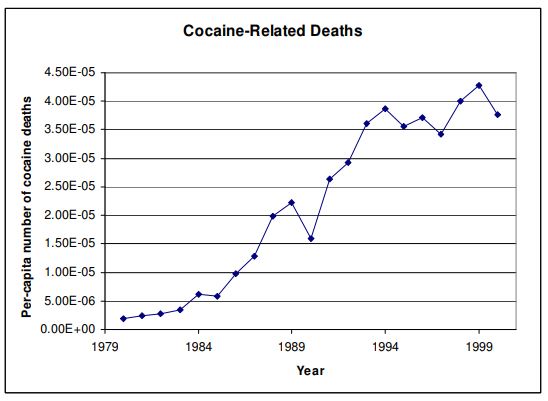

Cocaine-related data

Chart below shows how many cocaine-related deaths occurred for each person living in the U.S. for the years 1980-1999. This counts all forms of cocaine.

Data Source Roland G. Fryer, Jr/Harvard Univ Society of Fellows and NBER; Paul S. Heaton/Univ of Chicago; Steven D. Levitt/Univ of Chicago; Kevin M. Murphy/Univ of Chicago

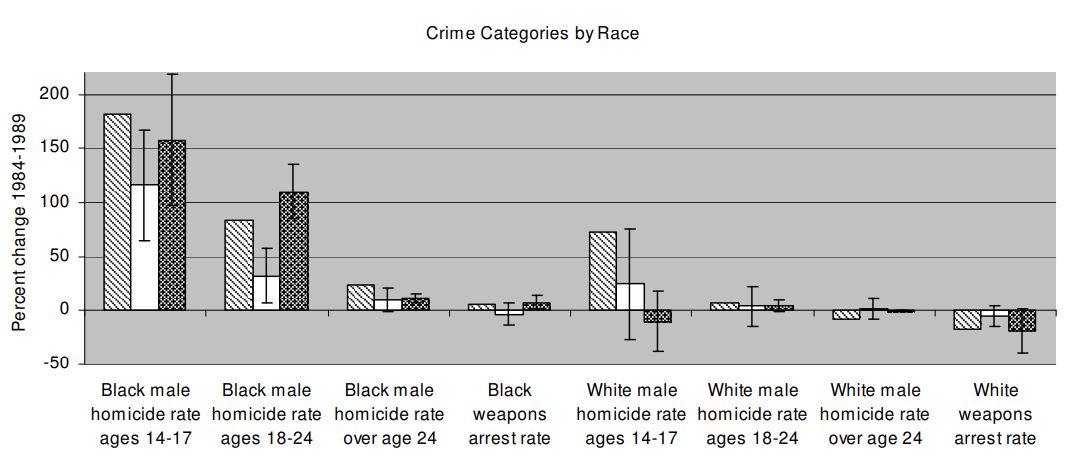

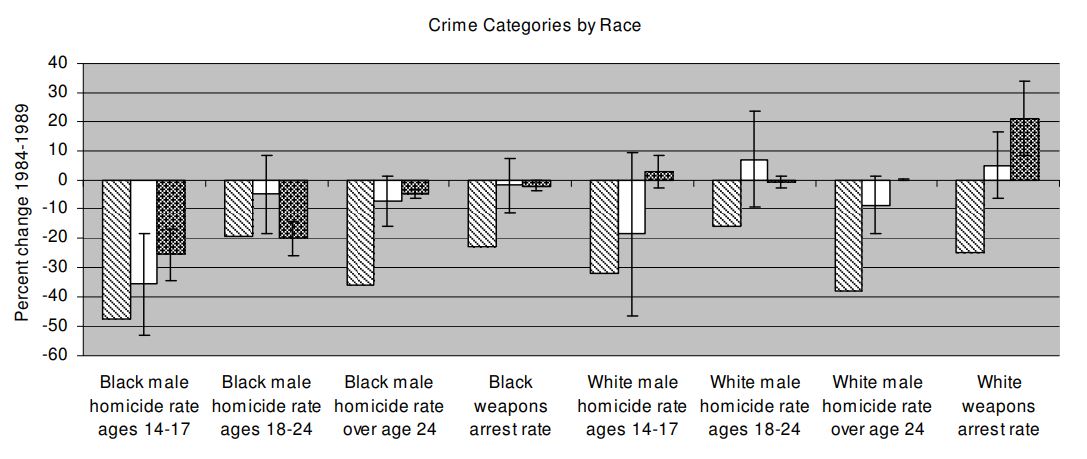

How the crack epidemic affected crime rates from 1984-1989. The chart figures depict population-weighted annual national averages using city-level data.

Data Source Roland G. Fryer, Jr/Harvard Univ Society of Fellows and NBER; Paul S. Heaton/Univ of Chicago; Steven D. Levitt/Univ of Chicago; Kevin M. Murphy/Univ of Chicago

How crime rates dramatically decrease for all crime types post-high-epidemic years

Actual Social Outcomes Changes and Predicted Changes as a Result of Crack from 1989-1999. City-Level Sample

Data Source Roland G. Fryer, Jr/Harvard Univ Society of Fellows and NBER; Paul S. Heaton/Univ of Chicago; Steven D. Levitt/Univ of Chicago; Kevin M. Murphy/Univ of Chicago

These opioid and cocaine-related datasets can not be used to make apples-to-apples comparisons on the number of overdose deaths. There is not enough comparative data to make an assessment on which drug epidemic was worst.

The opioid and crack epidemic takeaways:

- Most crack overdose deaths were black

- Most opioid overdose deaths have been white

- The crack epidemic is associated with a spike in crime in American cities– homicide, increased gang activity, prostitution

- The opioid epidemic is characterized by an epidemic in prescription opioid addiction and illicit opioid addiction

- The legal community’s response to the crack epidemic was generally to punish users and dealers with harsh prison sentencing

- The legal community’s initial response to the opioid crisis was generally to punish the users and dealers of illicit opioids. Eventually came laws to limit prescriptions, then local and state public health policy changes focusing more on sympathy for those addicted to opioids with ‘addiction as a disease’ narrative calling for medical treatment rather than punishment

- There is limited data on the exact number of crack cocaine deaths during the epidemic as all cocaine-related deaths were combined

- Public health and drug abuse sites agree that no drug epidemic has killed more people in the U.S. than opioids

- Despite softening attitudes towards opioid abusers, there have been no major public health policy changes to stem the number of deaths

Sources

Why Didn’t My Drug-Affected Family Get Any Sympathy?

Opioid Overdose Deaths by Race/Ethnicity

How Today’s Opioid Crisis is Similar to the Crack Cocaine Epidemic of 1980s

National Institute on Drug Abuse – Overdose Death Rates

The deadliness of the opioid epidemic has roots in America’s failed response to crack